This compelling book is comprised of powerful chapters that will strongly resonate with anyone in the world today. Anyone can understand the concept of willful blindness. Yet only those who see things as they really are in our current surreal reality will truly feel the full force of what is shared here.

Throughout this post, links will be provided to specific page numbers in the book, that will redirect readers to the online book loan feature in the (legal and legitimate) e-library hosted by the Internet Archive. This is a superb resource, it is completely free to use the service. ‘Loaning’ a book means that an actual physical book at the Internet Archive is taken out of circulation, and the images of the physical pages are available for your perusal for up to 14 days (renewable dependent on demand).

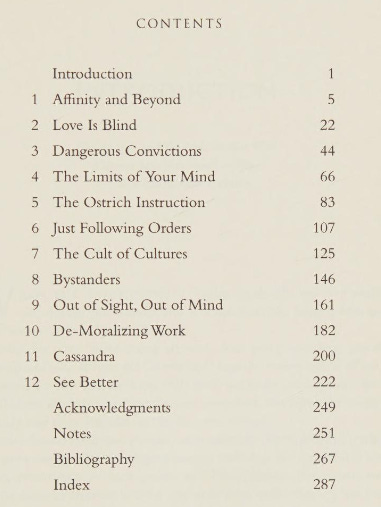

We will analyse excerpts from chapters 1 – 7:

Heffernan’s introduction cites a short story told by psychologist Philip Zimbardo, recounting his hospitalisation, aged 5 years old, due to double pneumonia and whooping cough.

“Kids,” he said, “were dying all over. And every morning, you’d wake up and ask, ‘Where did Charlie go?’ And the nurses would all say, ‘He went home.’ And we’d say, ‘Oh that’s great he went home!’ But we all knew the kids who ‘went home’ were dead. But here’s the thing, the only way to be hopeful was to deny the reality.”

Heffernan adds:

The problem arises when we use the same mechanism to deny uncomfortable truths that cry out for acknowledgement, debate, action, and change. Many, perhaps even most, of the greatest crimes have been committed not in the dark, hidden where no one could see them, but in full view of so many people who simply chose not to look and not to question.

Now, recall the countless stories we have read in the legacy media these past few years, whereby the family members of people who have died shortly after having the Covid-19 injection (often times officially and medically attributed to the injection), being quoted as saying ‘he would have still wanted everyone to get vaccinated’ or assigning blame elsewhere.

We few who can see, have all experienced the horrible dawning realisation that we are living through the greatest crimes ever committed in history, in full view of the global population. Yet the majority still remain willfully blind – also termed as willful ignorance, conscious avoidance, or deliberate indifference.

For clarity and posterity, these crimes include (but are not limited to):

We may think being blind makes us safer, when in fact it leaves us crippled, vulnerable, and powerless. But when we confront facts and fears, we achieve real power and unleash our capacity for change. –pg4

Most of us are familiar with this term when discussing relationships, for example, the long suffering wife that chooses not to see herself being treated like a doormat by an emotionally abusive husband.

The most common form of being blinded by love in Thailand amongst foreign men, comes in the form of the long distance relationship. The absent man supports his girlfriend financially, making quarterly visits to the kingdom, only to one day discover that she has another boyfriend living locally.

Cutting the other way, Thai women are often manipulated into giving away their wealth in so called ‘romance scams.’ The most notable case in history setting the world record at an eye-watering sum of 6.3 billion THB ($185,566,500 USD) being extracted from the target.

In late 2019 Essilor International discovered fraudulent fund transfers totaling 6.3 billion baht at its Thai unit, Essilor Manufacturing (Thailand). Chamanan Phetporee, chief finance officer of Essilor…was duped by a gang of criminals who invented ‘Andrew Chang’, an American medical officer based in Afghanistan who inherited large amounts of money and wanted to transfer those funds to Thailand.

In her desperation to believe in the idea of love with a fictitious man existing only in name, photos chosen by the scammers, promises, and correspondence, this lady became enthralled in the fantasy. After agreeing to buy a house for ‘Andrew’, the scammers came up with more stories to drain her accounts.

Heffernan extends this concept of love blindness beyond the individual:

Nations, institutions, individuals can all be blinded by love, by the need to believe themselves good and worthy and valued. We simply could not function if we believed ourselves to be otherwise. But when we are blind to the flaws and failings of what we love, we aren’t effective either…we make ourselves powerless when we pretend we don’t know. That’s the paradox of blindness: We think it will make us safe even as it puts us in danger. –pg42

In our current time of great dying, it can be challenging to discern which institutions have been wholly captured, versus which ones are blinded by their love for the greater good cause of safe and effective, obliviously carrying out crimes against humanity.

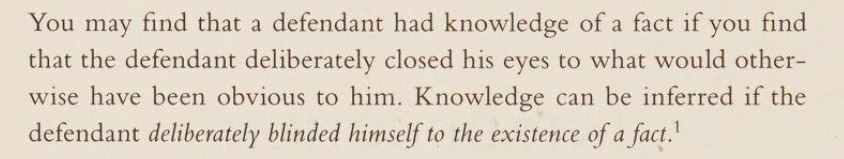

Do not conflate this analysis with sympathetic narration. All individuals and institutions that are willfully blind in the scamdemic era carry varying degrees of guilt, and by extension, culpability.

From the loving parent that has had their child injected, to the caring universities still mandating the gene therapy for students – then later claiming to not be responsible for something they could have known, or should have known, but strove not to see, is not a valid defense.

After all, willful blindness is used as a legal term.

Let us be mindful of the fanatical religious zeal, in which so many have applied their dangerous convictions – their subscription to the new normal ideology being synonymous with group derangement. Heffernan surmises this pertinently:

Ideology is a conceptual framework, it’s the way people deal with reality. Everyone has one. You have to. To exist, you need an ideology. – Alan Greenspan, October 23, 2008. Pg44

Cognitive neuroscientists examined ‘motivated reasoning’ – the process by which people adjust what they know to avoid bad feelings such as anxiety and guilt. The brain attempts to satisfy two kinds of constraints: cognitive constraints – a desire to filter information rationally – and emotional constraints, meaning the need to feel good about the information taken in.

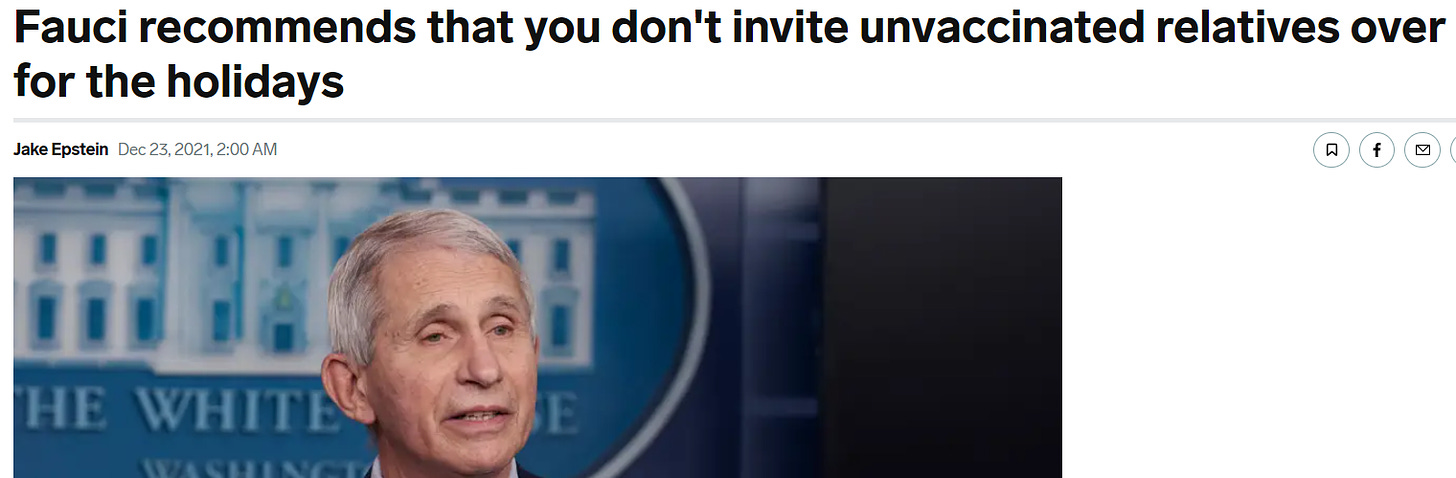

This brings to the fore recollections of the hardline lockdowners, whom became the strongest proponents for compulsory ‘vaccination’, and the ostracisation of the uninjected from partaking in society.

Their motivated reasoning rallied around the legacy media / government propaganda slogans such as ‘we’re in this together’. ‘getting vaccinated is the best way to protect yourself and others in your community’. The willfully blind would feel great about doing their part as they absorbed this filtered information in, thereby minimising any feelings of anxiety or guilt over the othering of the filthy, despicable ‘unvaccinated’.

He added that he hoped unvaccinated people would “put aside any ideological consideration” and get vaccinated to protect themselves and others.

“It’s the best thing for you and your family but also your societal responsibility to not allow yourself to be a vehicle for spread to someone else who might be very vulnerable,” he said.

Heartwarming stuff, isn’t it?

Heffernan also explains the concept of disconfirmation, which makes belief systems stronger. Disconfirmation, is when a belief system is temporarily shattered by an event or a fact, yet rather than snapping the individual / group out of their willful blindness, it reinforces it. This is because they do some mental gymnastics to make the new information fit with their delusion.

For example, the claims made about the injections being 100% effective at everything a ‘vaccine’ is supposed to do, to the now evident negative efficacy of murdering people. In between these two polar extremes, we had (and still have) the classic line:

It could have been worse, I could have been unvaccinated.

Time and again, we have seen people thank their lucky stars that they did not die, owing to their boosters, despite having ‘caught Covid’ for the umpteenth time, and being severely hospitalised.

Her diagnosis “was a shock, because I’m triple vaxxed, I haven’t been anywhere, I haven’t done anything,” as ABC reported her saying at the time. “It’s one of those things where you think, I’ve done everything I was supposed to do… Yeah, it doesn’t stop Omicron.”

Was it really a shock? In one sense, it may have been a shock deep inside the cognitively dissonant mind, questioning how and why this keeps happening. However, simultaneously, those pesky feelings of anxiety are quashed by the self proclamations of feeling good about ‘doing everything I was supposed to’.

This point has been extensively brought up by the new media, along with plentiful examples from countless historical atrocities. We shall instead focus on the underlying psychology, rather than the obviously invalid defense of justifying carrying out atrocities as a result of following orders.

Heffernan quotes Milgram, who carried out the shocking experiment, which famously demonstrated that ordinary people could be induced to deliver what they believed to be potentially fatal shocks to strangers on the say-so of an authority figure:

“There is no anger, vindictiveness, or hatred in those who shocked the victim. Men do become angry; they do act hatefully and explode in rage against others. But not here. Something far more dangerous is revealed: the capacity for man to abandon his humanity, indeed the inevitability that he does so, as he merges his unique personality into larger institutional structures.”-Pg112

The author proceeds to distinguish between obedience and conformity. Whereas obedience involves complying with the orders of a formal authority, conformity is the action of someone who adopts the habits, routines, and language of his peers, who have no special right to direct his behaviour.

Your correspondent would like to add that from experience and observation, many individuals who have been just following orders, have failed to see discrimination against the uninjected, at the point that they lose their humanity. Although they recognise that they have been rewarded rather than punished for their personal choice, that is seen as the natural and obvious choice.

When pressed for their opinion on the uninjected having been discriminated against, they are still often blind to this entirely. They might say “but that was your choice, you chose to not be able to travel.”

It is truly frightening and heartbreaking to witness these statements uttered from those who you love.

At this stage of the book, Heffernan draws sharp comparisons between conformity and obedience. Paraphrasing her deductions here, the author states that conformity is voluntary and implicit, distinguishing it from obedience, which comes from following orders, which are explicit. The following excerpt has been edited and paraphrased for brevity:

There was a study conducted in 2005 by neuroscientist Gregory Berns and a team of researchers at Emory University. Using fMRI technology, the objective was to study the brain at the point at which it conforms. Participants were asked to compare three dimensional objects to decide if two were the same, in another experiment they knew what their fellow participants had decided, and in the final test, they cast their vote after knowing what the computer had decided.

The scientists weren’t looking to discover whether they would conform. They were interested in what kind of brain activity was involved. If activity in the prefrontal cortex was dominant, it would indicate that the conformity was the result of conscious decision making.

Whereas if the activity centered in the occipital and parietal regions of the brain, that would suggest that conformity was an act of perception – social influence had altered what the volunteer saw. When they conformed, there was no activity in the prefrontal cortex – meaning that a conscious decision was not being made.

The brain’s activity centered on those areas of the brain responsible for perception. In other words, knowing what the group saw changed what the participants saw; they became blind to the differences.

The scientists concluded that the areas of the brain responsible for perception are altered by social influences. What we see depends on what others see. That was a remarkable enough finding. But several other insights emerged from this experiment.

Knowledge of the group’s decision seemed to reduce the mental load on the volunteers; less thinking took place when they knew what the others thought. A good match could stop thinking because it felt right. So instead of the group benefitting from the collective wisdom of many, in fact what it got was a reduced thoughtfulness from each one.

Furthermore, in the rarer examples of a participant taking an independent stand against the crowd, something else happened; the amygdala, the area of the brain that governs emotions, became highly active. Something tantamount to distress seemed to take place. Independence, it seems, comes at a high cost…-pg135

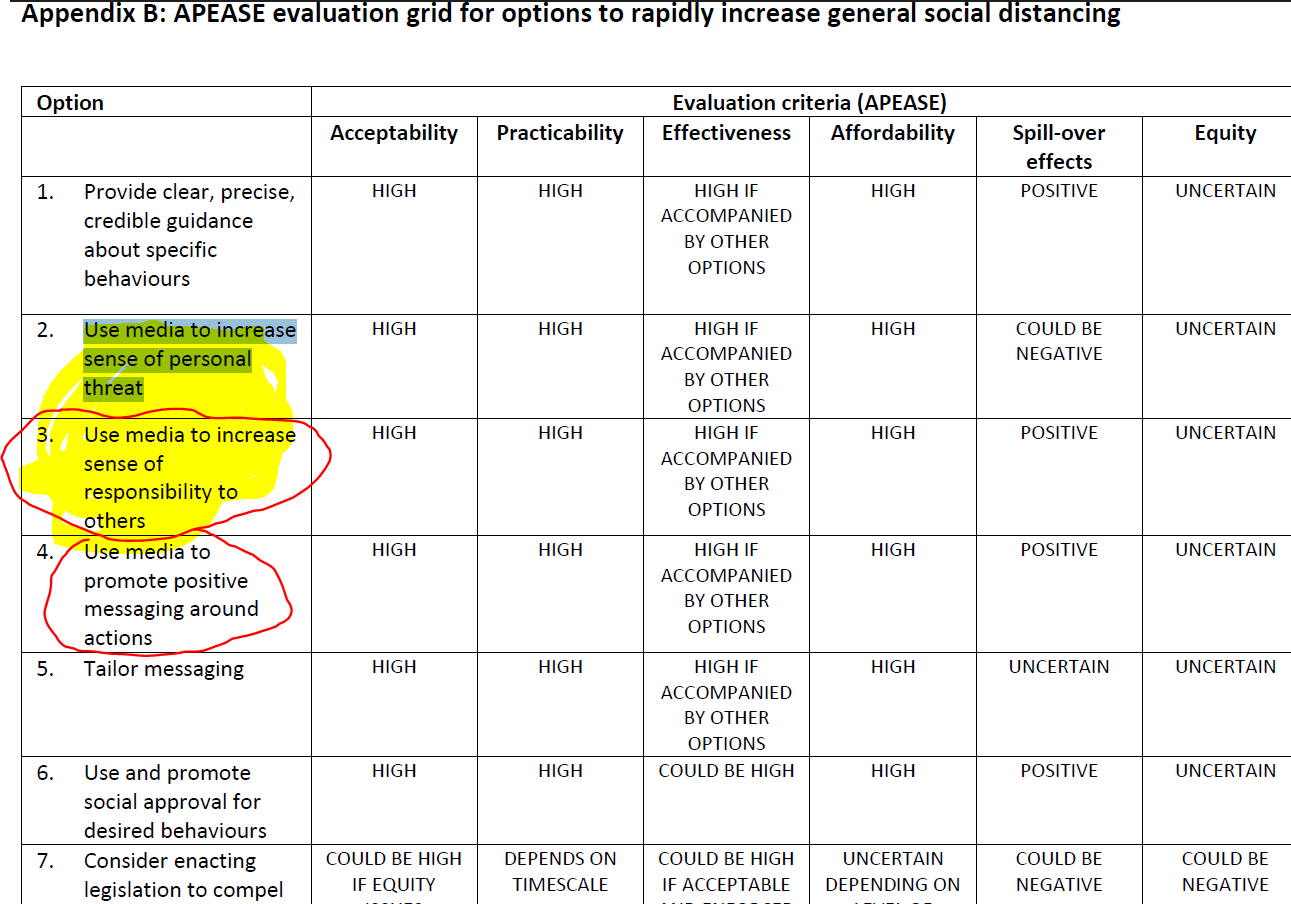

After processing this and applying the findings to our current reality, we may infer the meaning behind the lack of conscious decision making that led to people not only taking the first injection, but going back for boosters again and again. For the UK’s aggressive applied behavioural psychology techniques, directed by SAGE and SPI-B, the sense of duty to community and country was heavily played upon. This manipulated people’s decision making process, as they were led to believe that their peers had already decided to ‘get the jab’, suggesting that conformity was an act of perception, just like in Bern’s experiment.

In closing, below is a video from Margaret Heffernan’s Ted Talk on The dangers of “willful blindness” – hard hitting and illuminating. If you prefer to avoid YouTube, the video can be found on Odysee here. The full transcript can be read here.